It appears that this Cicada Bug Coloring & Activity Book is the second most popular cicada book on Amazon. This took me by surprise. I have not read it, so I cannot vouch for its quality.

Here’s the top 5 that I see:

It appears that this Cicada Bug Coloring & Activity Book is the second most popular cicada book on Amazon. This took me by surprise. I have not read it, so I cannot vouch for its quality.

Here’s the top 5 that I see:

This is a web version of this old PDF.

There is an “old wives tale” that says that if you see a “W” on a cicada’s wing that there will be war, and if you see a “P” there will be peace. What you see is in the eyes of the “bugholder”, but I’ve personally only seen a “W”, which almost seems logical, because there is always a war going on somewhere.

“Will you miss me when I’m gone?”

As I write this, the Brood XIX emergence is all but over, and Brood XIII has about two weeks left to go.

So what’s next? Well, I’ll tell you.

You can help cicada researchers by uploading your photos to iNaturalist or the Cicada Safari app.

iNaturalist is excellent for all animals — plus plants and fungi — not just cicadas. You will find yourself using it all year long. Cicada Safari is specifically for cicadas.

There are more to cicadas that just Periodical cicadas.

Cicadas exist on every continent except for Antarctica, and in every State in the U.S. except for Hawaii and Alaska!

Learn about the most-common cicadas that live in the same areas as periodical cicadas, and then learn about the variety of cicadas found around the world.

Saving cicada skins (molts/shells) and wings is easy. Just keep them dry.

Preserving Periodical cicadas can be challenging because their eye colors fade and because they’re fatty and smell.

If you want to preserve eye colors, keeping them in alcohol seems to work best.

Some people dip them in acetone to mitigate the smell from decaying fat, but I’ve never tried it.

Otherwise, keep them dry and in a cedar box. I use silica gel packs to keep them dry. Cedar repels small insects that will eat your cicada collection. Moth balls work as well to keep tiny insects away from your collection.

If you want to pin your cicadas, so the wings are spread out, you have to do it while the cicadas are still moist. Plenty of places have supplies, like Carolina Biological Supply. I’ve softened hard cicadas by placing them in Tupperware/Rubbermaid containers with moist paper towels and a moth ball to prevent mold.

Make a scrapbook or photo album of your cicada memories.

This is something I do every year, though I tend to mix it up with non-cicada photos as well.

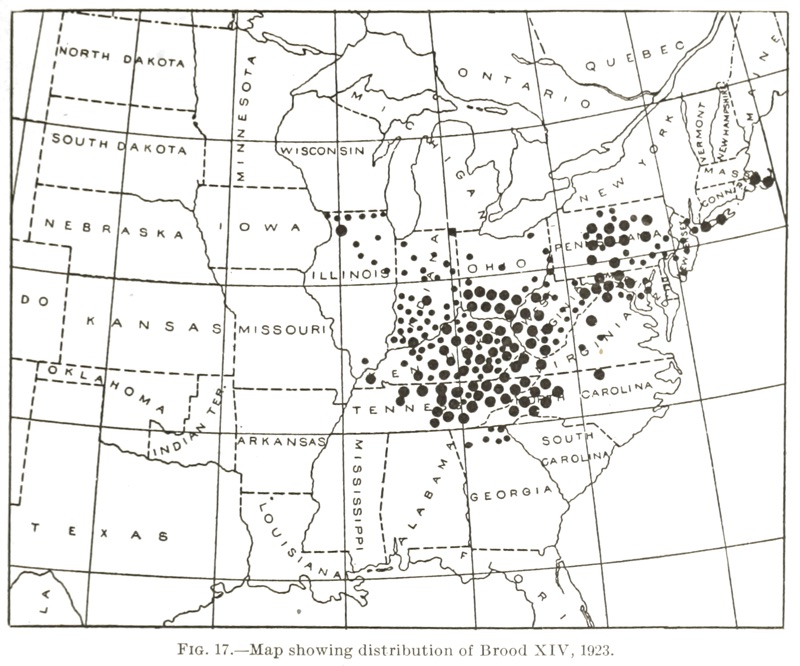

Periodical cicada Brood XIV (14) will emerge in the spring of 2025 in Georgia, Kentucky, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia. The last time this brood emerged was in 2008. Special note: removing Maryland from the list at the request of the State Entomologist of Maryland. There might be some Brood X stragglers in Maryland.

It looks like the first adult Magicicada was signed in Tennessee. See the report on iNaturalist. This could be a straggler from another brood.

Millions of these Magicicada cicada insects:

Usually beginning in May and ending in late June. These cicadas emerge approximately when the soil 8″ beneath the ground reaches approximately 64 degrees Fahrenheit. Above ground temperatures in the 70’s-80’s help warm the soil to that point. A warm rain will often trigger an emergence.

Other tips: these cicadas will emerge after the trees have grown leaves, and, according to my own observation, around the same time Iris flowers bloom.

Georgia: iNaturalist Live Map. Counties: Fannin, Lumpkin, Rabun, Union.

Indiana: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking the southern part of Indiana, by the Ohio River. Counties: Crawford, Harrison, Perry.

Kentucky: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking most of Kentucky east of U.S. Route 41, with major hot-spots along the Ohio river. Counties: Anderson, Barren, Bath, Bell, Bourbon, Boyd, Bracken, Campbell, Carter, Clinton, Edmonson, Fayette, Franklin, Floyd, Gallatin, Grant, Hardin, Harrison, Henderson, LaRue, Laurel, Leslie, Logan, Madison, McCreary, Montgomery, Nelson, Nicholas, Pendleton, Pike, Pulaski, Rowan, Scott, Shelby, Whitley. Cities: Adairville, Bowling Green, Corbin, Flemingsburg, Frankfort, Greensburg, Hazard, Jeffersontown (J-Town), Louisville, Radcliff, Richmond, Valley Station.

Massachusetts: iNaturalist Live Map. Counties: Barnstable, Plymouth. Locations: (western half of) Cape Cod.

New Jersey: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking southern New Jersey, where the Jersey Devil lives (he might have ate them all up). Counties: Atlantic, Camden, Ocean. Cities: Linwood, Manchester Township, Winslow Township.

New York: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking Long Island. Counties: Nassau, Suffolk. New York cities: East Setauket and Dix Hills (thanks Elias Bonaros).

North Carolina: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking western North Carolina, particularly areas heavily impacted by Hurricane Helene. It will be interesting to see if the cicadas were impacted as well, as flooding may have washed away their underground tunnels and habitat. Counties: Buncombe, Burke, Caldwell, Catawba, Henderson, McDowell, Mitchell, Wilkes. North Carolina cities: Asheville, Moravian Falls, north-west of Nashville, Wilkesboro. The first reported adult cicada was found in Leicester, NC on 4/22.

Ohio: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking south-western Ohio, with the hottest spots just east of Cincinnati. This is the homeland of cicada-experts Gene Kritsky and Roy Troutman, and world-famous botanist Matt Berger. Counties: Adams, Brown, Butler, Clermont, Clinton, Gallia, Hamilton, Highland, Ross, Warren. Cities: Batavia, Blue Ash, Cincinnati area, Indian Hill, Loveland, Maderia, Mariemont, Milford, Miami Twp.

Pennsylvania: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking central Pennsylvania, and random locations toward the east.Adams, Berks, Blair, Cambria, Centre, Clearfield, Clinton, Cumberland, Huntingdon, Lackawanna, Luzerne, Lycoming, Mifflin, Montour, Northumberland, Snyder, Union. Pennsylvania cities: Bear Gap, Elverson.

Tennessee: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking north of Nashville, north-west of Chattanooga and in random places in the eastern half of the state. Counties: Bledsoe, Blount, Campbell, Carter, Cheatham, Claiborne, Cocke, Coffee, Cumberland, Davidson, Grainger, Grundy, Hancock, Hawkins, Jefferson, Marion, Putnam, Roane, Robertson, Rutherford, Sevier, Sumner, Unicoi, Williamson. Cities: Cades Cove, Goodlettsville, Hampton, Muddy Pond. The first reported adult cicada was found in Nashville on 4/25.

Virginia: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking western Virginia, and mostly the part tucked under Kentucky. Counties: Botetourt, Lee, Russell, Scott, Smyth, Tazewell, Wise.

West Virginia: iNaturalist Live Map. We’re talking the area west of Interstate 77 (I-77), bordered by Kentucky and Ohio. Counties: Cabell, Kanawha, Mason, Mingo, Putnam, Wyoming. West Virginia cities: Huntington.

*City data comes from May 2008 and June 2008 blog comments. County locations are historical and may no-longer be accurate.

Experts (Gaye Williams, State Entomologist of Maryland, John Cooley of UCONN) have confirmed that there will be no Brood XIV cicadas for Maryland. That said, there will be some stragglers from Brood X. You can look for reports of stragglers using this iNaturalist map.

* Although county locations may no longer be accurate, I like to keep them on the page in case someone discovers a small, secret or unknown population of these cicadas. People might be disappointed, but we want to know for sure that the cicadas are (or are not) thriving in historical locations. This is the cicada researcher’s dilemma: either focus on the guaranteed/sure shot locations for the general public to enjoy, or include the obscure, relic locations so we do not miss out on rare cicada sightings. Cicadas @ UCONN talks about the relationship between the different broods — Brood XIV and Brood X are closely related geographically and genetically. You might find a Brood X straggler emerging 4 years late, and mistake it for Brood XIV. If a large number (large enough to sustain future emergences) of Brood X makes the 4-year “JUMP” to be in synch with Brood XIV, they technically become Brood XIV (and the reverse is true).

This map comes from the 1907 publication Marlatt, C.L. 1907. The periodical cicada. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Bureau of Entomology.

This is an interesting story from LinkedIn. The folks at Nel PreTech Corporation created a CT scan of a female Magicicada!

Today I was digging in a flower garden that is mostly inhabited by thick-stemmed Montauk Daisies, and I found many cicada nymphs. The nearest tree is about 25 feet away — I guess any type of root will suffice for some cicadas.

They seem weak and disorientated, which makes sense since they’ve lived underground their whole lives.

There are Magicicada (Brood II), Neotibicen tibicen, Neotibicen lyricen, and Neotibicen linnei in the yard. I haven’t investigated which species these are yet, but I think it’s likely they’re not Magicicada because they were relatively large (bigger than a penny) and Brood II is 6 years away.

Many of you will remember Samuel Orr from his film Return of the Cicadas.

He has a new Instagram account and website.

Sam is well known for his cicada photography and videography.

Return of the Cicadas from motionkicker on Vimeo.

People ask, “Can periodical cicada singing damage hearing”? It all depends on how long you expose yourself to their song, and how close your ears are to the insect. Invest in some quality ear plugs if you are concerned. Consult a medical professional, of course. Get a Sound Level Meter.

Periodical cicada choruses are often in the 80–85db range, which the CDC says “You may feel very annoyed” and “Damage to hearing possible after 2 hours of exposure”:

If you spend a long time outside during a chorus, your ears will probably ring for hours after. That is my personal experience.

Placed directly on a microphone, I have observed periodical cicadas get as loud as 111.4db. According to the CDC, that is close enough to cause hearing damage in less than 2 minutes. Do not place male cicadas on your ear! Do not put your head right next to the tree branches where they’re singing.

Check out this video of Magicicada sound levels measured by an EXTECH 407730 Sound Level Meter:

How to avoid hearing them?

I’ve exposed myself to hundreds of hours of cicada songs. I’ve also gone to hundreds of concerts and listened to a lot of rowdy music over the years. My hearing is not great, but it is probably not due to cicadas.

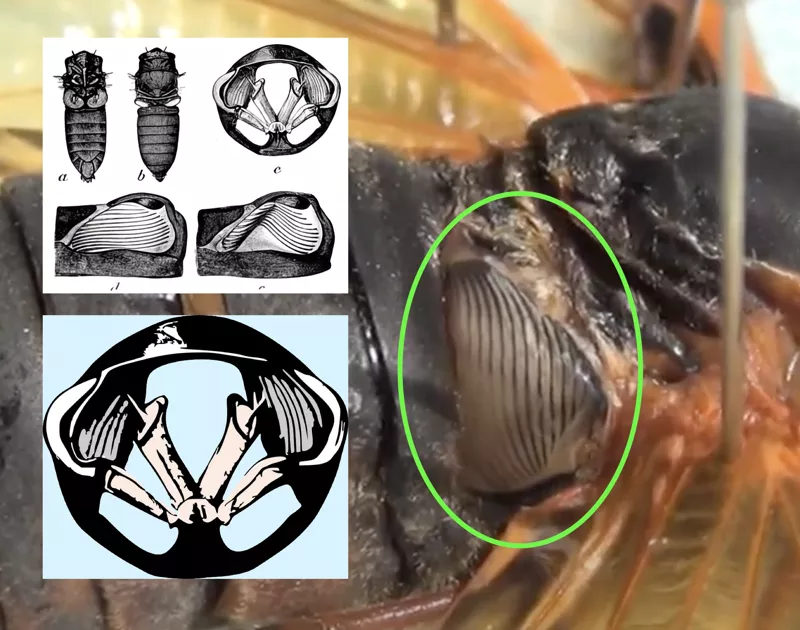

It is worth mentioning that only male cicadas sing. Females make noise by flicking their wings, but they are not as loud as the males. Males have organs called tymbals that vibrate creating their signature sound.

Here are illustrations and a photo of a Magicicada’s tymbals. They have one on each side of their body:

So what is the loudest cicada? According to the University of Florida Insect Book of World Records, “The African cicada, Brevisana brevis (Homoptera: Cicadidae) produces a calling song with a mean sound pressure level of 106.7 decibels at a distance of 50cm.” The loudest cicada in the United States, using the same methodology, is Diceroprocta apache (Davis) at 106.2db at 50cm.

I need to take measurements of Magicicada from 50cm to make a comparison. The measurements I’ve taken are in the midst of a large chorus with cicadas about a meter to 20 meters away, which falls in the 80-85db range; or directly on the mic, which gets into the 109-111db range. Your results may vary.

One phenomenal behavior of Magicicada periodical cicadas is they “straggle”, meaning they emerge earlier or later than the year they are expected. Typically they emerge 1 or 4 years before they’re supposed to emerge.

Brood XXIII is expected to emerge in four years in 2028, but enough are emerging in 2024 for cicada researchers like Chris Simon to take notice! She let us know about the stragglers on May 8th.

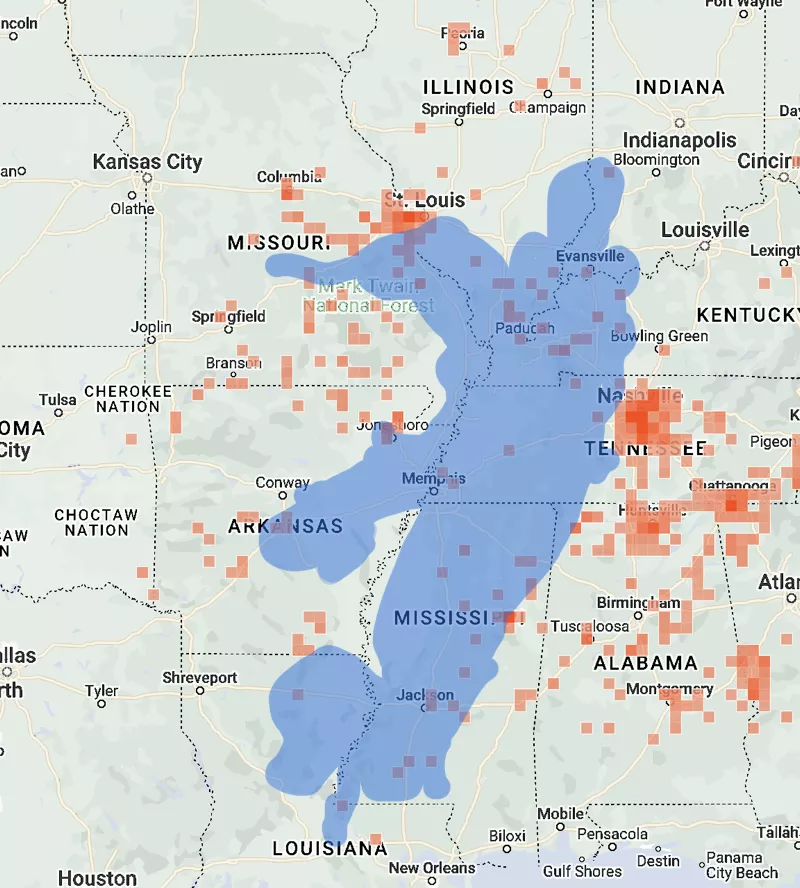

Brood XXIII is found in Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee. This is not a perfect map (it overlaps with Brood XIX), but XXIII cicadas will show up in that area.

Arkansas: Bayou Deview Wildlife Management Area, Poinsett County, Devalls Bluff, Harrisburg, Holland Bottoms, Jacksonville, Jonesboro, Knox Co., Lake Hogue, Lake Poinsett State Park, Little Rock, and Wynne.

Illinois: Anna, Carbondale, Carterville, Chester, Clinton Lake, Marissa and Robinson.

Indiana: Harmonie State Park, Hymera, Leanne, Richland, Sullivan And Posey Counties.

Kentucky: Benton, Calvert City, Gilbertsville, Henry County, Murray, and Paducah.

Louisiana: Bastrop, Choudrant, Grayson and West Monroe.

Mississippi: Alva, Arlington, Booneville, Brandon, Clinton, Corinth, Desoto County, Florence, French Camp, Hernando, Holcomb, Houlka, Jackson, New Albany, Oxford, Potts Camp, Silver Creek, Tishomingo, and Water Valley.

Tennessee: Atoka, Benton, Cordova, Henry County, Huntingdon, Jackson, Lavinia, Leach, Lexington, McNeary County, Memphis, Paris, Savannah, and Speedwell.

Here’s a blue overlay of there Brood XXIII emerges from the UCONN map on the iNaturalist data (as of May 5th):

Surrounding the blue area on the west and east is Brood XIX and north will be Brood XIII.

More info:

I created a new iNaturalist project called the Magicicada Flagging Project to track tree flagging damage by Magicicada cicadas.

Upload a tree or branch with flagging to iNaturalist, add it to the Magicicada Flagging Project, and when it asks you if the observation has “Magicicada Flagging” select “yes”.

When Magicicada cicadas lay eggs in the branches of trees (ovipositing) branches may become damaged or die which causes the leaves to turn brown. This is called flagging. Magicicadas, depending on their location, oviposit between late April through to the end of June. Flagging will appear in the weeks following ovipositing. Leaves will remain brown throughout the year.

The project leverages the observation field Magicicada Flagging set to yes.

The project works regardless of whether the organism is identified as a type of tree (oak, chestnut, etc.) or a Magicicada cicada. Most people identify trees with flagging as a “Magicicada” but I would not want to take away the option to allow people to identify a tree (oak, chestnut, etc.) over the type of cicada that did the damage.

There is a similar observation field for cicada presence set to flagging/oviposition scars, but it’s not specific to Magicicada and oviposition scars do not always accompany flagging. I do encourage you to use this observation field as well!

![]()