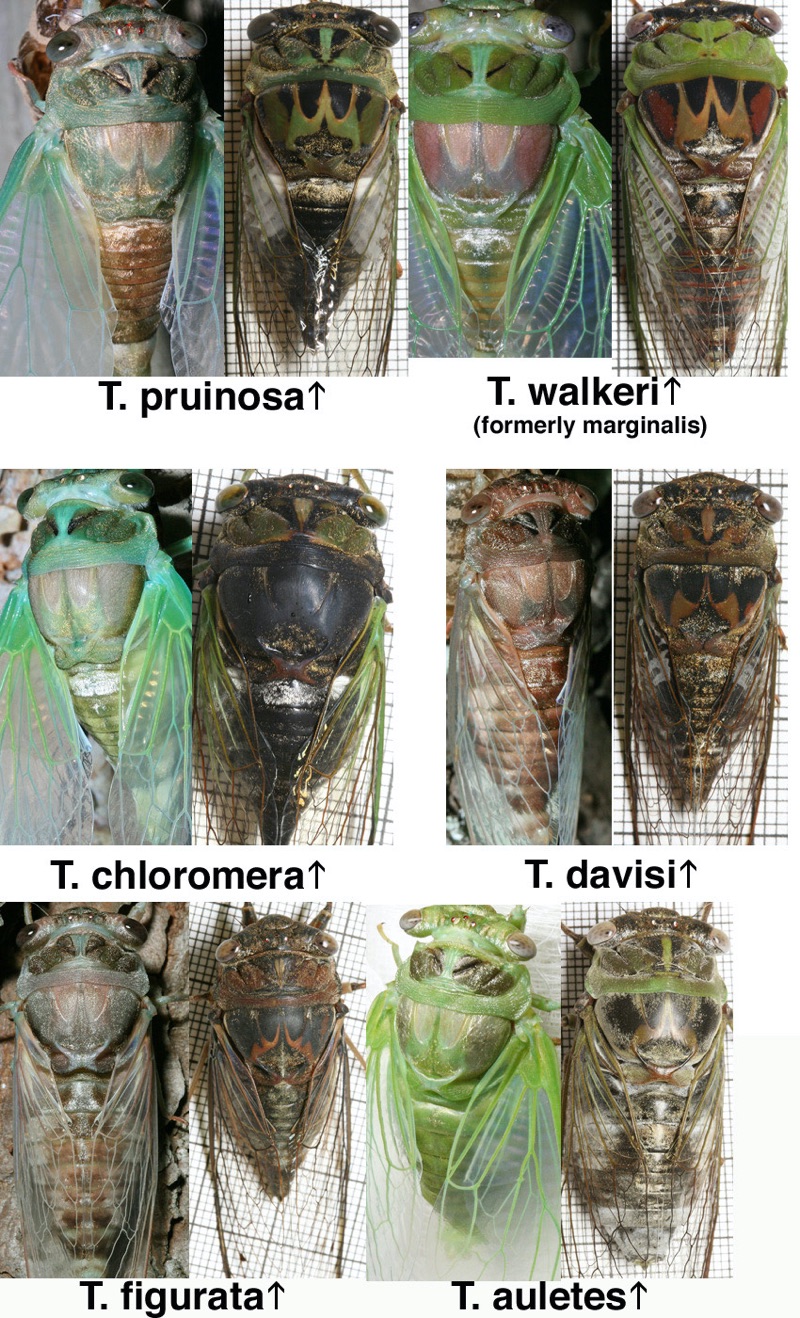

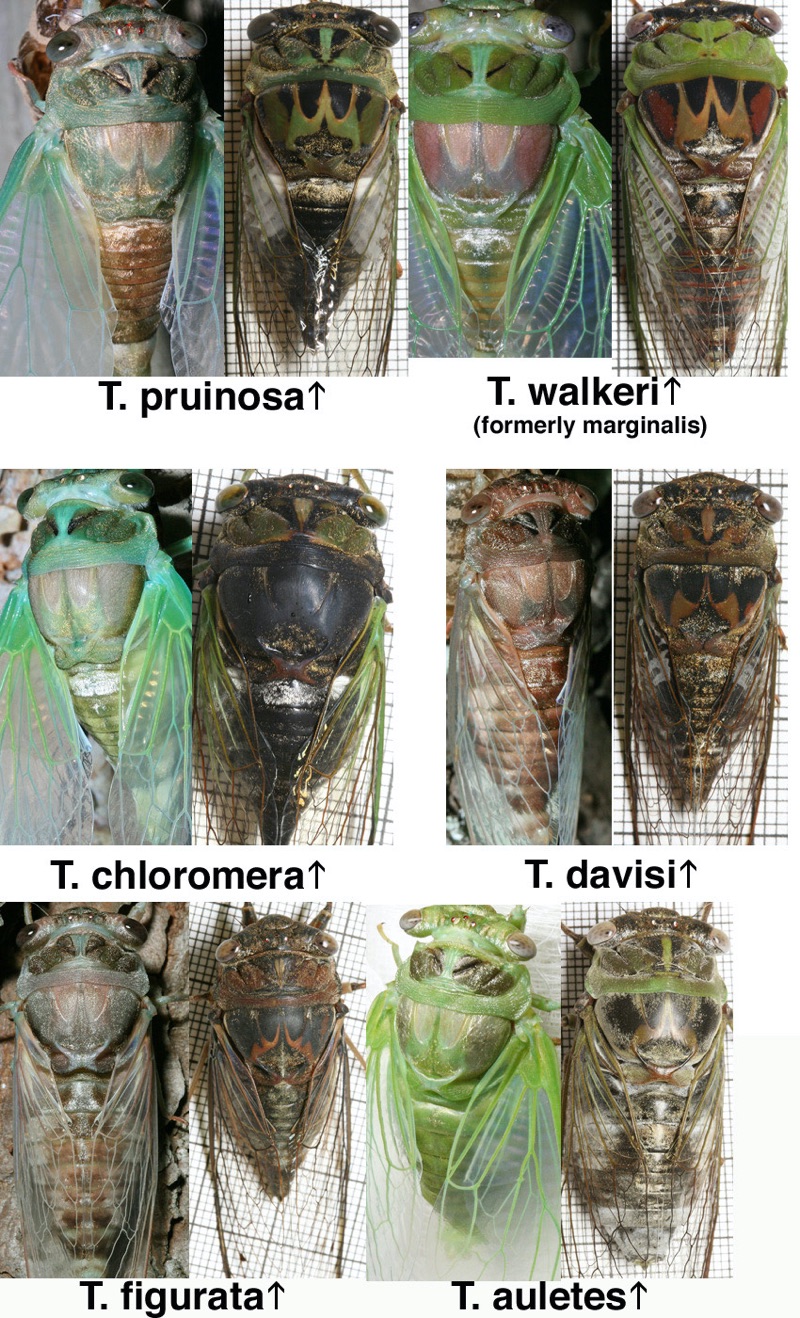

Paul Krombholz has come through with an awesome guide to identifying Tibicens just after they have molted. Click the image below for an even larger version. Note that the genus of these cicadas has changed to either Megatibicen or Neotibicen — notes below.

Notes on the species from Paul:

N. pruinosus [formerly T. pruinosa]—Newly molted adult has darker mesonotum (top of mesothorax) than the very common T. chloromera. Abdomen is a golden orange color. Older adult has dark olive on lateral sides of mesonotum, lighter green below the “arches”.

M. pronotalis (formerly walkeri, marginalis)—Quite large. The reddish brown color can be seen on the mesonotum of newly molted adult. Older adult has solid green pronotum (top of prothorax) and red-brown markings on sides of mesonotum. Below the “arches” the mesonotum color can range from carmel to green. Head is black between the eyes.

N. tibicen [T. chloromerus, T. chloromera]—has large, swollen mesonotum, quite pale in a newly molted adult and almost entirely black in an older adult. Individuals from east coast can have large russet patches on sides of mesonotum. The white, lateral :”hip patches” on the anteriormost abdominal segment are always present, but the midline white area seen in my picture is sometimes absent.

N. davisi—Small. This is a variable species, but all have an oversized head that is strongly curved, giving it a ‘hammerhead’ appearance. Newly molted individuals are usually brown with blueish wing veins that will become brown, but some have more green in wing veins. Some may have pale mesonotums that will become mostly black. Older adults vary from brownish to olive to green markings on pronotum and mesonotum.

M. figuratus [formerly T. figurata]—a largish entirely brown cicada. Newly molted adult has a pink-brown coloration with some blueish hints. Older adult has chestnut-brown markings and no green anywhere. The Head is not very wide in relation to the rest of the body. The small cell at the base of the forewing is black.

M. auletes—a large, wide-bodied cicada. The newly molted adult is very green, but the older adult loses most of the green, usually retaining an olive posterior flange of the pronotum. The dorsal abdomen of the adult has a lot of powdery white on the anterior and posterior segments with a darker band in between.

From my own photos, here’s a sequence of photos of a Neotibicen tibicen tibicen as its colors develop.

Here’s a comparison of two teneral Neotibicen linnei. Note the variation in colors — one green, one pink — from the same grove of trees in New Jersey. Color can vary a lot!