Summer is here now, so it is time for annual species of cicadas. See which types of cicadas are in your area.

If you experienced Brood X stragglers this spring, it’s not to late report the location where you saw them to Cicadas @ UCONN (formerly Magicicada.org). In the Ohio area, send your cicada photos of Mount St. Joseph University.

Other updates can be found in the comments.

What’s the deal with these amazing insects?

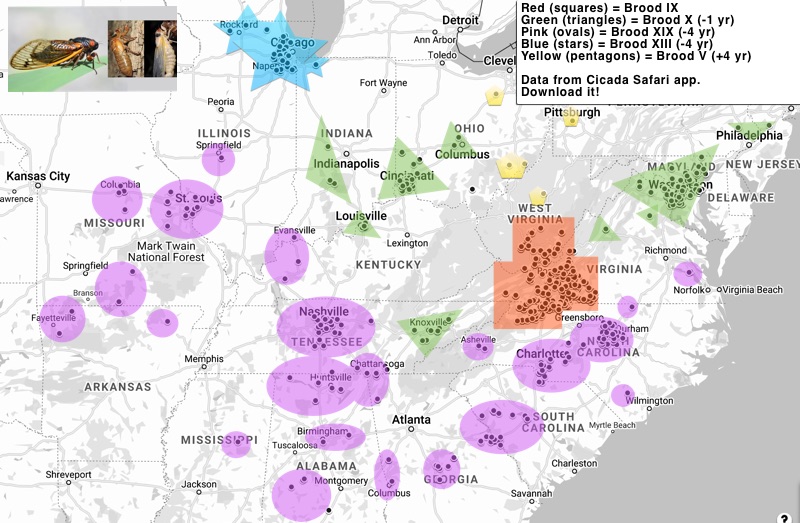

This year “precursors” to Brood X are emerging or will emerge in small to large numbers in D.C., Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York (Long Island), North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. Cicadas @ UCONN has the most up-to-date map from Brood X.

Note: because of the significant number of cicadas emerging ahead of time, this might be an acceleration event. Periodical cicada accelerations occur when a significant group of an established brood emerge in years ahead of the main brood, and sometimes the accelerated group is able to reproduce and create what is essentially a new brood. Brood VI was likely part of Brood X at one point of time1. We’ll have to see if the Brood X stragglers are able to survive predation, and reproduce in significant numbers to sustain future populations. They are certainly trying.

Some more info to impress your friends with:

These are the species you might hear/see:

- Magicicada septendecim

- Magicicada cassini

- Magicicada septendecula

Don’t panic! Less that one percent of a Brood straggles. If you had 10,000 cicadas in your yard back in 2004, you can expect a less-frightening or more manageable dozens or hundreds (okay, maybe 1,000s). 🙂

Brood VI also emerges this year?

Brood VI also emerged this year in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. These cicadas emerged on schedule, and are not stragglers. It is believed that Brood VI descended from Brood X through acceleration (mentioned above).

Brood VI compared to Brood X:

The data comes from Cicadas @ UCONN (formerly Magicicada.org).

What are stragglers, and why do they straggle

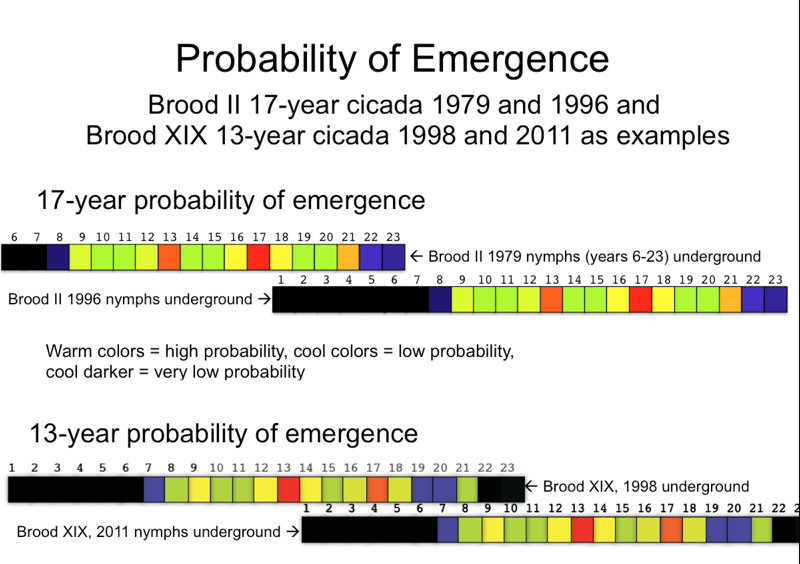

Stragglers are periodical cicadas that emerge in years before or after the brood they belong to is expected to emerge. Typically 17-year periodical cicadas emerge 4 years early (see the probability chart). While stragglers might not produce enough offspring to produce future generations, straggling is something periodical cicadas do — it is hard-wired into their DNA. The 4-year interval is also typical.

Stragglers are not a new phenomenon. William T. Davis documented accelerations of cicada populations back in the 1800s, which was reported by C.L. Marlatt in the 1898 document The Periodical Cicada. An Account Of Cicada Septendecim, Its Natural Enemies And The Means Of Preventing Its Injury.

Mr. W. T. Davis records the occurrence of scattering individuals on Staten Island in both 1890 and 1892, neither of which is a Cicada year. These may have been of accelerated or retarded individuals, but possibly represent either remnants of broods or insignificant broods not hitherto recorded.

In the case of W. T. Davis’s observations, Brood II would have emerged in 1894 in Staten Island, so 1890 would have been a 4-year straggler/processor/acceleration, and 1892 a rare 2-year acceleration.

The term “straggler” throws people off because most people are familiar with the definition of straggler that means “something that falls behind the main group”. These cicadas are clearly ahead of the main group, not falling behind. Straggle can also mean “to wander from the direct course or way” (Merriam-Webster), “to trail off from others of its kind” (Merriam-Webster). In terms of cicadas, scientists and naturalists have been using the term “straggler” for over a century, so it has stuck around. For now, don’t worry about the term, just know that it means periodical cicadas that are not emerging on schedule.

More information on stragglers and accelerations.

Climate and Stragglers

Dr. Gene Kritsky, in this recent article, is quoted as saying “[c]limate changes are behind the premature debut”. Visit Gene’s website.

It makes sense that climate variations would trigger periodical cicadas to emerge ahead of time. Periodical cicadas take cues from the seasonal cycles of their host trees. An unusual climate event, like a hot fall or winter, might cause trees to signal cicadas that additional years have passed, and cause them to shift to emerge early. In the paper, How 17-year cicadas keep track of time, Richard Karban was able to show that you can speed up the time it takes for a periodical cicada to emerge by artificially altering the seasonal cycles of their host trees2. It’s likely that the Brood X stragglers emerging now were set on their path to emerging 4 years early not this year or the last, but many years ago.

Metropolitan areas like Washington D.C., called “HEAT ISLANDS” (read this article), can often be much hotter than surrounding rural areas due to human activity. The effects of living within a heat island may have disrupted the seasonal cycles of the cicadas’ host trees, and therefore the cicadas themselves. Localized climate change will be considered as a contributing factor to their early emergence. If we find considerably fewer stragglers in rural areas than city areas, then we could draw a conclusion that local climates are contributing to straggling.

Other than climate (in the long term), weather (in the short term), and a natural propensity to straggle or accelerate, population density is another reason why cicadas will straggle. If there is a high density of them underground, vying for limited resources, some might emerge a year or so before or after the main Brood.

References:

1 Monte Lloyd &J o Ann White. Sympatry of Periodical Cicada Broods and the Hypothetical Four-Year Acceleration. Evolution, Vol. 30, No. 4. (Dec., 1976), pp. 786-801.

2 Richard Karban, Carrie A. Black and Steven A. Weinbaum. How 17-year cicadas keep track of time. Ecology Letters, (2000) 3: 253-256.