Brood V will next emerge in 2033.

This page was last updated in 2016.

Brood V (5) 17-year cicadas have emerged, this spring of 2016, in Maryland, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia & West Virginia.

Brood V (5) 17-year cicadas have emerged, this spring of 2016, in Maryland, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia & West Virginia.

Latest Updates:

(7/4/16): It’s a wrap! I’m sure there are some periodical cicadas hanging on out there, but for the most part, the emergence should be over. I hope you had fun.

(6/26/16): By now you should see (and hear) sharp declines in cicada populations. They’ll be gone in most places by July 4th. You should start to see Flagging of tree limbs where the cicadas lay their eggs. This is a natural part of the process.

New: Use our checklist to keep track of your Brood V experience!

Gene Kritsky has updated his book “In Your Backyard: Periodical Cicadas“. It is available for the low price of $4.99 for Kindle and Kindle readers. Totally worth it.

About Brood V:

The cicada species that will emerge are Magicicada cassinii (Fisher, 1852), Magicicada septendecim (Linnaeus, 1758), and Magicicada septendecula Alexander and Moore, 1962. These periodical cicadas have a 17-year life cycle. The last time they emerged was 1999.

When: Generally speaking, these cicadas will begin to emerge when the soil 8″ beneath the ground reaches 64 degrees Fahrenheit. A nice, warm rain will often trigger an emergence. So, definitely May, but something might happen in April if we have a particularly hot spring.

Locations where they are likely to emerge:

This data comes from the Cicada Central Magicicada Database (RIP) and other sources.

Although the cicadas will emerge in MD, NY, OH, PA, VA, and WV, the area is limited and patchy. No Brood V cicadas for D.C., Cincinnati, or NYC (people have asked). Their range is closer to this map (with cicadas in the orange areas):

Maryland:

Counties: Garrett.

New York:

Specific locations in L.I.:

- Wildwood State Park – Confirmed!

Counties: Suffolk (Long Island).

Ohio:

Specific locations in Ohio:

- The emergence should be good in the south eastern part of the state and in Summit, Medina, and southern Cuyahoga counties1.

- Hocking State Forest, Hocking county, which is where James Edward Heath performed his investigation of periodical cicada Thermal Synchronization2.

- Tar Hollow State Forest, in Laurelville, Hocking County, Ohio.

- Strouds Run State Park, in Canaan Township, Athens County.

- Athens, Athens County, Ohio

- Findley State Park, Lorain County, Ohio.

Counties: Ashland, Ashtabula, Athens, Belmont, Carroll, Columbiana, Coshocton, Crawford, Cuyahoga, Fairfield, Franklin, Gallia, Geauga, Guernsey, Harrison, Hocking, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Knox, Lake, Lawrence, Licking, Lorain, Mahoning, Medina, Meigs, Muskingum, Noble, Ottawa, Perry, Pickaway, Pike, Portage, Richland, Ross, Sandusky, Scioto, Seneca, Stark, Summit, Trumbull, Tuscarawas, Vinton, Washington, Wayne

Thanks to Roy Troutman, John Cooley, Chris Simon and Gene Kritsky for the tips!

Pennsylvania:

Counties: Allegheny, Fayette, Greene, Somerset, Washington, Westmoreland

Virginia:

Specific locations in Virginia:

- Douthat State Park, in Bath & Allegheny County Virginia.

Counties: Allegheny, Augusta, Bath, Highland, Richmond, Rockingham, Shenandoah

West Virginia:

Counties: Barbour, Boone, Braxton, Brooke, Cabell, Calhoun, Clay, Doddridge, Fayette, Gilmer, Grant, Greenbrier, Hampshire, Hancock, Hardy, Harrison, Jackson, Kanawha, Lewis, Marion, Marshall, Mason, Monongalia, Nicholas, Ohio, Pendleton, Pocahontas, Preston, Putnam, Raleigh, Randolph, Ritchie, Roane, Taylor, Tyler, Upshur, Webster, Wetzel, Wirt, Wood

Learn more about Brood V:

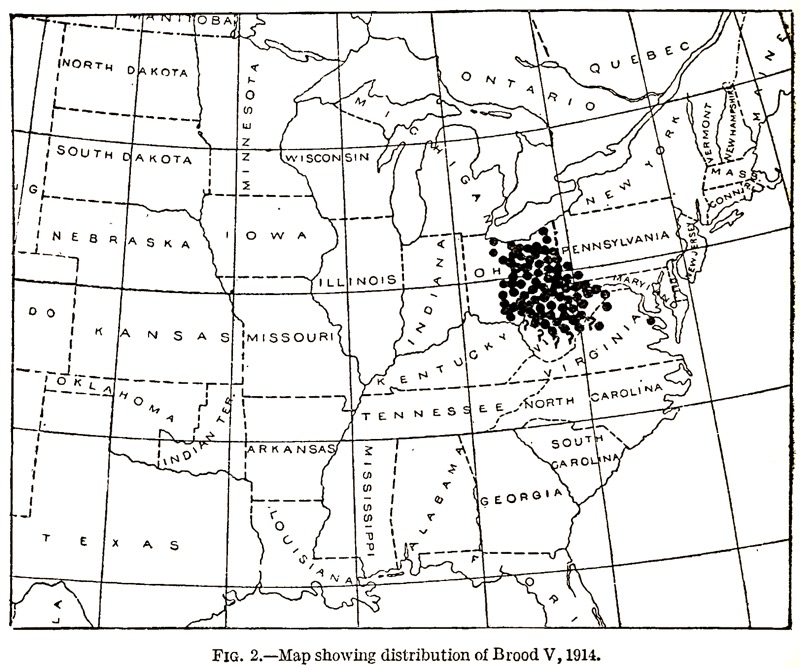

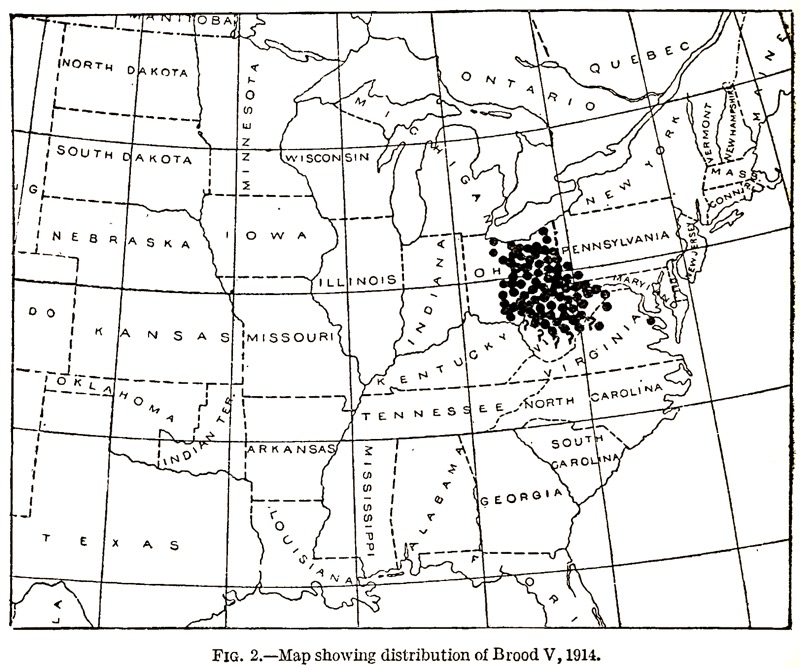

For historical purposes, Here’s C. L. Marlatt’s map from 1914:

Marlatt, C.L.. 1914. The periodical cicada in 1914. United States. Bureau of Entomology

1 Kritsky, G., J. Smith, and N. T. Gallagher. 1999. The 1999 emergence of the periodical cicada in Ohio (Homoptera: Cicadidae: Magicicada spp. Brood V). Ohio Biological Survey Notes 2:43-47.

2 Thermal Synchronization of Emergence in Periodical “17-year” Cicadas (Homoptera, Cicadidae, Magicicada) by James Edward Heath, American Midland Naturalist, Vol.80, No. 2. (Oct., 1968), pp. 440-448.

* The map is based on this map from the Wikimedia Commons by Lokal_Profil.

Brood V (5) 17-year cicadas have emerged, this spring of 2016, in Maryland, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia & West Virginia.

Brood V (5) 17-year cicadas have emerged, this spring of 2016, in Maryland, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia & West Virginia.