Jim Occi has contributed photos to Cicada Mania since the 2004 Brood X emergence.

Here are 5 photos from the recent Brood X emergence in New Jersey:

More photos by Jim:

Jim Occi has contributed photos to Cicada Mania since the 2004 Brood X emergence.

Here are 5 photos from the recent Brood X emergence in New Jersey:

More photos by Jim:

The Staten Island Museum is home to William T. Davis’ massive collection of cicadas and other insects. A new exhibition of insect-based art opens on July 16 at the Staten Island Museum, by artist Jennifer Angus.

Art by Jennifer Angus.

Here’s the press release.

For Immediate Release

Jennifer Angus: Magicicada

New exhibition of insect-based art opens July 16 at the Staten Island Museum(Staten Island, NY — June 29, 2021) As Brood X wanes, cicadas emerge anew at the Staten Island Museum with Jennifer Angus: Magicicada, a new exhibition opening Friday, July 16 2021 and running through May 22, 2022.

Magicicada is an immersive exhibit featuring exquisite ornamental patterns and imaginative vignettes created by artist Jennifer Angus using hundreds of preserved insects. Taking inspiration from the Museum’s collection of cicadas- one of the world’s largest- the installation will feature over two dozen species of cicada, including Brood X periodical cicadas, or Magicicadas, collected during the 2021 emergence.

“Cicadas, and Magicicada in particular, have a deep connection and meaning to the Staten Island Museum. Founder William T. Davis was the cicada expert during his lifetime and was even the one who coined the name Magicicada, capturing the wonder of the periodical cicadas’ mass emergences and long disappearances. It is especially poignant that this exhibit is opening as we are also remerging into the world after a time of darkness. I am hopeful that it can bring people a sense of joy and wonder after a time of profound loss.” Colleen Evans, Staten Island Museum Director of Natural Science.

Using responsibly collected and preserved specimens, Angus creates site-specific installations with hundreds of insects pinned directly to walls, creating patterns reminiscent of textiles or wallpaper. Up close, the installations reveal themselves to be comprised of actual insects, often species that are not traditionally considered beautiful. Angus’s installations also include Victorian-style insect dioramas in antique furniture and bell jars. Her work motivates viewers to find beauty in unexpected places and to understand the importance of insects and other creatures to our world.

In preparation for this exhibit, Angus spent time in the Museum’s extensive natural history collections to help shape the finished show. Select objects and specimens from the natural science collection, including retired collection storage and historic taxidermy, will be featured throughout the gallery amidst Angus’s fanciful arthropod arrangements. During the spring Brood X emergence, she traveled to Princeton, NJ along with the Museum’s Director of Natural Science, Colleen Evans, and Joseph Yoon from Brooklyn Bugs to observe and collect cicadas for the show.

Artist Jennifer Angus states: “I often say that the meat and potatoes of my installations are cicadas. They come big and small. Tropical species often can have colourful wings causing many people to assume they are moths, but unlike those insects, cicadas are tough, hardy creatures standing up to repeated use in my art installations. I could not have been more delighted when the SIM contacted me, and I learned of founder William T. Davis’ passion for cicadas which were an under documented species in his day. I have had the privilege of exploring the SIM’s collection, the one of the largest of cicadas in the world, and have been inspired by these mysterious creatures who spend most of their lives underground but upon emerging let us all know of their presence with loud calls. That Brood X periodical cicadas have emerged this year as well is a joyous event and has brought considerable notice to cicadas. I deeply appreciate the assistance provided by the SIM’s staff in working with me to celebrate the cicada.”

Magicicada is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Staten Island Museum is supported in part by public funds provided through the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs and by the New York State Council on the Arts.

Exhibition Related Programing

Brood X Sounding Off: Saturday, July 17, 2 pm — 3 pm

Cicada Talk with Colleen Evans, Director of Natural ScienceVirtual Artist Talk: Sunday, September 19, 3 pm-4 pm

Registration RequiredStaten Island Museum is located on the grounds of Snug Harbor Cultural Center, 1000 Richmond Terrace, Building A, Staten Island, NY 10301.

About the Artist:

Jennifer Angus is a professor in the Design Studies department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she teaches in the Textile and Apparel Design Program. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and her Master of Fine Arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Jennifer has exhibited work throughout the world and at galleries such as the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington D.C. and the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, PA.

Art by Jennifer Angus.

Here’s a video from Jin Yoshimura who researches periodical cicadas.

The Evolutionary Origin of Periodical Cicadas: A Sci-Fi Story:

The Evolutionary Origin of Periodical Cicadas: A Sci-Fi Story:

Periodical cicadas are known for their unique 17- and 13-year life cycles and mass emergence events. This mystery of why they would have evolved these two prime-numbered life cycles has attracted many biologists and mathematicians. Dr. Yoshimura will explore this phenomenon

Okanagana aurantiaca Davis, 1917.

A. Male uncus not hooked at the extremity, sometimes sinuate.

B. Expanse of fore wings more than 50 mm.

CC. The base of the fore and hind wings not of the usual orange-red variegated with black.

Body and wing venation nearly entirely orange; basal cell of fore wings clear; a black band between the eyes, and a conspicuous dorsal band of the same color extending from the hind margin of the pronotum to the end of the abdomen.

Family: Cicadidae

Subfamily: Cicadettinae

Tribe: Tibicinini

Subtribe: Tibicinina

Genus: Okanagana

Species: Okanagana aurantiaca Davis, 1917.

The Princeton Battlefield (historical location of one of George Washington’s battles) has always been a great place to find Brood X periodical cicadas.

Here are a few photos I took last weekend:

A female Magicicada septendecim with white eyes & costal wing margin mating:

A female Magicicada septendecim with white eyes & costal wing margin:

Magicicada with beige eyes:

Many, many exit holes:

Triple exit holes in mud (kinda looks like a skull):

Egg nests carved into branches by the cicadas ovipositor:

Here’s a short 2021 update for the Platypedia putnami survey at Horsetooth Mountain Open Space, west of Fort Collins, Colorado. 2021 is turning out to be a very large emergence for this cicada, and it’s not through yet! The survey transect goes from the trailhead parking lot to Horsetooth Falls. Although the first exuvia found was on May 22, 2021, the bulk of the exuvia, so far, have emerged (153 of 201 exuvia) June 5-8th. “Clicking” of adults can be heard in many areas, but is concentrated in certain sites.

Tim McNary

Fort Collins, COHere are the mega data on exuvia found each year:

2009- 136 exuvia

2010- 0

2011- 3

2012- 2

2013- 179

2014- 0

2015- 12

2016- 0

2017- 0

2018- 13

2019- 2

2020- 0

2021- 201 (exuvia through June 8, 2021)

Links:

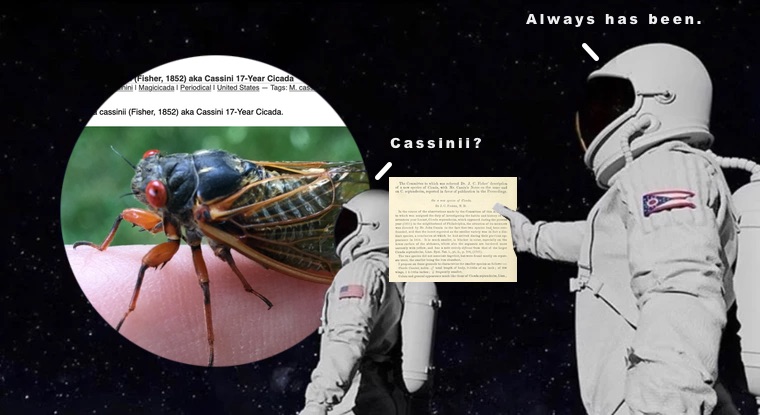

Update (4/10/2022) David C. Marshall published a paper arguing for the use of the name Magicicada cassini (one i): Marshall, David C. On the spelling of the name of Cassin’s 17-Year Cicada, Magicicada cassini (Fisher, 1852) (Hemiptera: Cicadidae). 2022. Zootaxa 5125 (2): 241–245. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5125.2.8

My friend asked “when did Magicicada cassini become Magicicada cassinii“? Over the years, the spelling Magicicada cassini with the single “i” at the end became the most commonly used form of the name, but the original spelling ended with “ii”.

(Ignore this meme):

The original name of the cicada was Cicada Cassinii, named by Dr. J.C. Fischer. The genus changed to Magicicada (no dispute there), but cassinii stuck around, although it was shortened to cassini over the years (originally in Walker 1969: 8941) in many publications. There is no reason why we shouldn’t call the cicada Magicicada cassinii, as far as I know.

In the 1850s, Dr.J.C. Fisher, M.D. proposed the name Cicada cassinii for this cicada, named for ornithologist John Cassin, who described the cicada in detail. See Vol V, 1850 & 1851 of the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, pages 272-275. Here’s a link to the document. Quotes below:

The Committee to which was referred Dr. J. C. Fisher’s description of a new species of Cicada, with Mr. Cassin’s Notes on the same and on C. septendecim, reported in favor of publication in the Proceedings.

On a new species of Cicada.

By J. C. Fisher, M. D.In the course of the observations made by the Committee of this Academy, to which was assigned the duty of investigating the habits and history of the seventeen year Locust, Cicada septendecim, which appeared during the present year (1851) in the neighborhood of Philadelphia, the attention of its members was directed by Mr. John Cassin to the fact that two species had been confounded, and that the insect regarded as the smaller variety was in fact a distinct species, a conclusion at which he had arrived during their previous appearance in 1834. It is much smaller, is blacker in color, especially on the lower surface of the abdomen, where also the segments are bordered more narrowly with yellow, and has a note entirely different from that of the larger Cicada septendecim, Linn. Syst. Nat. i., pt. ii., p. 708, (1767).

The two species did not associate together, but were found mostly on separate trees, the smaller being the less abundant.

I propose on these grounds to characterize the smaller species as follows: —

Cicada Cassinii, nobis. (♂ total length of body, 9-10ths of an inch; of the wings, 1 2/10ths inches; ♀ frequently smaller.

Colors and general appearance much like those of Cicada septendecim, Linn., but darker, and the segments of the abdomen below are more narrowly bordered with yellow. Note different to that of C. septendecim, and more like that of some of the grasshoppers. Inhabits the neighborhood of Philadelphia, appearing in the winged or perfect state at intervals of seventeen years.

Note on the above species of Cicada, and on the Cicada septendecim, Linn-

By John Cassin.

There are two distinct and easily recognized species of Cicada which appear at intervals of seventeen years, and both of which were observed in this neighborhood, especially in the woods at Powelton, during the present year. I saw them in Delaware county, Pennsylvania, in 1834, and their entire specific distinctness I have insisted on through good and evil report for the last seventeen years.

It was therefore highly gratifying to me to have an opportunity of calling the attention of the gentlemen of this Academy to the smaller species which Professor Fisher has done me the honor of naming as above, and particularly to its note. This is quite different from the prolonged and loud scream of the larger species, (which is C. septendecim, Linn.) and begins with an introductory clip, clip, quite peculiar. No disposition to associate with each other exists between the two species, and although I have seen both on the same tree, yet most frequently they were entirely separated, and occupied different parts of the woods. In 1834, I observed the smaller species in localities which were somewhat favorably situated for moisture, but during the present year it occurred in localities as varied as those of the other and larger species. At Powelton it was very abundant in an orchard of apple trees on the most elevated part of the estate, and also on trees in the adjacent woods.

That the smaller species preferred low grounds was the observation of Dr. Hildreth, of Marietta, Ohio, who, in an article on the Cicada septendecim, in Silliman’s Journal, xviii. p. 47, (1830) has the following paragraph: — ” There appeared to be two varieties of the Cicada, one smaller than the other; there was also a striking difference in their notes. The smaller variety was more common in the bottom lands and the larger in the hills.”

The size and the peculiar note are the most striking characters of the smaller species, otherwise it much resembles the larger. The consideration of its claims to specific distinction involves the general problem of specific character, which is difficult in theory, but practically is readily solved. An animal which constantly perpetuates its kind, or in other words reproduces itself

either exactly or within a demonstrable range of variation, is a species. These two Cicadas do not associate together as varieties commonly do. Of the very numerous instances in which the phenomenon introductory to propagation has been observed this year, in the course of the particular attention paid to these insects by gentlemen of this Academy, not one case occurred in which the male and female of the two insects were seen together. They are distinct species.The appearance of the Cicada septendecim in various localities at different

periods, each terminating intervals of seventeen years, for instance in Ohio in 1846 and in Eastern Pennsylvania in 1851, is a matter of remarkable interest.Many independent ranges or provinces are known to exist in the United States,

and they are now ascertained to be so numerous that this species probably appears in some part of the country every year. Assuming all that part of North America in which it has ever been observed to be its zoological province, how are the sub-provinces and different times of appearance to be accounted for? Are all those sub-provinces to be regarded as the theatres of independent creations? Do the facts demonstrate that the same species may exist in provinces which may be presumed to have had different eras of origin?It would be a curious fact, and one of important application, that exactly the same species can inhabit provinces having independent creations, and if, too, as in the case of this insect, it should be clearly impossible for it to have extended from one province to another.

Or, can it be possible that every distinct district in which the Cicada appear is really an entomological province, and that entomological provinces in this part of North America are quite restricted in extent, as has been observed by Dr. Le Conte in California? (Communicated by that gentleman to the American Association for the advancement of Science at its meeting in August, 1851.)

Those sub-provinces may have relations to geologic changes. Having the extraordinary characteristic necessity of remaining in the earth for seventeen years, as a fact in the history of this insect, may it be possible to infer that geologic changes have effected the difference in the times of its appearance, or that so short periods as fractions of seventeen years have been of geologic importance throughout the range of the Cicadas?

The Cicada septendecim has appeared in the vicinity of Philadelphia, at intervals of seventeen years, certainly since 1715. There has been, it appears, no variation of temperature, nor causes accidental nor other since that date sufficient to affect its habits in any perceptible degree. It is stated in Clay’s Swedish Annals, to have appeared in May, 1715, in this neighborhood, (which, so far as I know, is the earliest authentic record 😉 punctually in the same month, every seventeeth year, now certainly for nearly one hundred and fifty years, has this extraordinary insect been known to make its visit. No causes have affected it during that period, not even so far as relates to the month in which it appears.

Passing, I would observe that so far as relates to the neighborhood of Philadelphia, the Cicada septendecim clearly had not a fair start with the year 1, — anno mundi of the commonly received chronology. If it had had, the sum produced by 1851X4004 — 1 ought to divide by 17 without a remainder, which it will not do, — more insignificant facts than which have troubled schoolmen.

I have never seen any animals more entirely stupid than the seventeen year Locusts. They make no effort to escape, but allow themselves to be captured with perfect passiveness, thus reminding one of the lameness of animals in countries where they are not molested by enemies. All animals of as high grade of organization as these insects, acquire instincts from impressions made by the presence of danger and otherwise, which they transmit to their offspring. The young Fox of today is undoubtedly superior to his juvenile progenitor of a century since. The cicadas have acquired no such instinct. Their short life of maturity above the surface of the earth does not appear to be of sufficient duration for such to be formed and impressed on their posterity.

In short, it appears to me that the study of these insects, and the examination of their separate ranges, might result in conclusions of extraordinary importance, especially relative to modern views of the distribution of animals.

No animal is more easily traced. In other aspects, too, they present interesting points for study, perhaps of general interest in zoological science.

A couple of interesting things about their texts:

1 Allen F. Sanborn. Catalogue of the Cicadoidea (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha). 2014. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-416647-9.00001-2

The question I saw most this year (2021) was “what are the black spots on the back of cicadas for”? The people asking this question are specifically talking about Magicicada cicadas that have recently molted and are still white/cream colored and soft (teneral from the Latin word “tenen” meaning soft).

The area of the cicada where the black spots appear is called the pronotum — “pro”, meaning before in Greek, and “notum”, meaning the back, also in Greek. Before the back.

The spots contain a pigment that will gradually spread throughout a cicada body as it hardens, and transforms from white to black.

People speculate that the two black spots resemble eyes, and that might scare away predators. This might be possible, but I haven’t read anything to substantiate the hypothesis.

Brood X has emerged in Princeton, New Jersey, but the weather is currently not great for cicadas: less than 50°F and rainy. Undaunted, I visited Princeton yesterday to observe Magicicada cicada behavior on a cold, rainy day.

I arrived at Princeton Battleground State Park around 3:30 PM and immediately head to the short trees and tall weeds, like honeysuckle, that line the perimeter of the park. I was pleased to see hundreds of cicadas clinging to the leaves, stems, and branches of the plants — seemingly without extra effort or discomfort. Many were weighted down by droplets of rain, which seemed to roll off their bodies and bead on their wings like translucent pearls.

Even though temperatures were below 50°F I did hear an occasional distress call, and saw plenty of cicadas mating — perhaps they started mating before the rain and cold weather began. No flying. No calls, chorusing, or wing flicks.

Other than thousands of seemingly healthy but (patient) cicadas hanging from vegetation, there were plenty of malformed cicadas on the trunks of larger trees, and piles of exuvia and corpses circling tree trunks. The air around trees stank like ammonia and rotting fat and meat — not unlike a dumpster behind a burger restaurant.

I saw mostly Magicicada septendecim and some Magicicada cassini. No apparent Magicicada septendecula. I saw just one M. Septendecim infected with Massospora cicadina fungus. While there was plenty of avian activity in the area, I did not see any birds or other creatures feast on the docile or dead cicada — maybe I scared them away — maybe their appetites were satiated.

Cicadas dripping with rain:

Cicadas mating:

M. Septendecim infected with Massospora cicadina fungus:

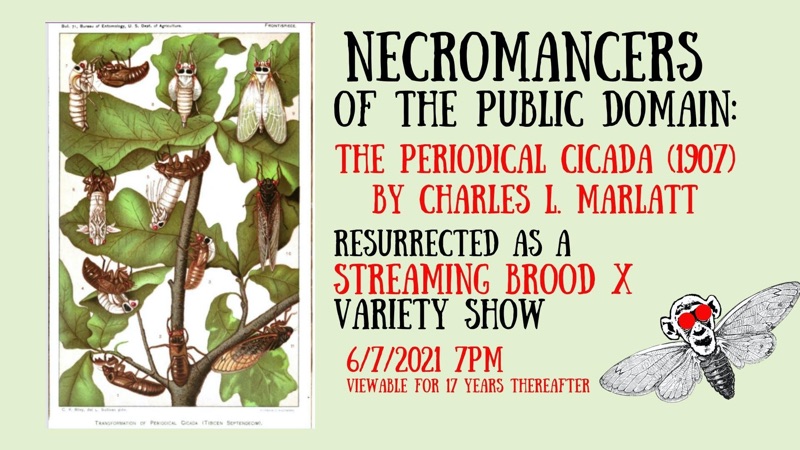

THE PERIODICAL CICADA resurrected as a free streaming cicada-themed variety show.

Theater of the Apes celebrates the emergence of BROOD X with a FREE 17-year Cicada-themed Virtual Variety Show.

June 7th, 7 PM EST. tune in: