This is my third, and possibly final, article on identifying Neotibicen, using the information on this website. Read the other articles, Identifying Neotibicen and Megatibicen (formerly Neotibicen).

Identifying the smaller Neotibicen is no easy task — with two exceptions.

The two easy ones are:

1) Neotibicen superbus, aka the Superb Cicada, because it looks like no other cicada in this group. It is pea green with bright yellow arches on its mesonotum. No other Neotibicen shares that coloration. No other cicada in the group sounds quite like it either.

Photo by Sloan Childers from 2005.

2) Neotibicen latifasciatus, aka Coastal Scissors Grinder Cicada, because it has a white X (pruinose) on its back. Otherwise, it looks like four other cicadas, kinda like four more, and sounds like three others.

While I’ve never heard an actual scissor being sharpened with a grinder, it must sound like the repetitive, rhythmic, short grinding sounds like cicada makes. Grind, Grind, Grind, Grind.

Photo by me of Bill Reynolds’ collection.

The rest of the small Neotibicen closely resemble each other enough to make many scratch their heads in wonder. BugGuide.net organizes these cicadas into four groups4: the “Green Tibicen Species” (Tibicen is the old genus name for these cicadas), “Southern Dog-day Cicadas”, “Swamp Cicadas”/”The chloromerus Group”, and the “Lyric Cicadas”/”The lyricen Group”. I’ll use these groups for this article for consistency sake. These groups are also closely related genetically1, although Neotibicen similaris, which BugGuide puts under “Southern Dog-day Cicadas”, is a bit of an outlier1. Tables below might be a bit overwhelming — but they help to accurately align the similarities between these cicadas.

As you browse this page, if you click the cicada’s name you’ll be brought to a page that features more information about that cicada, including sound files, location information, links to other websites, and often more photos and video. When in doubt: visit the BugGuide Dog Day Cicada page.

The Green Neotibicen

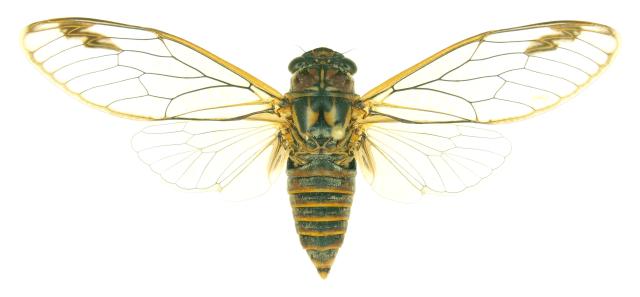

These Neotibicen all share green markings on their pronotum, mesonotum, and pronotal collars. Find a Neotibicen with a green collar, and there’s a good chance it is one of these. As you can see, these insects are well camouflaged for adult life in trees.

Photo credits l to r: Roy Trountman, Tom Lehmkuhl , Paul Krombholz, me.

From Davis 1918 =”Dorsum (top) of abdomen shining black with a broad pruinose (white, frosty) mark each side on segment three; blackened area on the underside of abdomen more in the nature of an even stripe”.

| Cicada |

Sounds Like |

Looks Like |

Looks Kind of Like |

| N. canicularis (Harris, 1841) aka Dog-day Cicada

The canicularis varies the most in terms of coloration. Some are very dark, with more black than green, and others have an even amount of green and black.

Sounds like an angle grinder tool grinding something.

|

N. auriferus

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

|

N. auriferus

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

N. latifasciatus

N. linnei

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. robinsonianus

N. winnemanna

|

| N. latifasciatus (Davis, 1915) aka Coastal Scissor(s) Grinder Cicada

If the cicada has a white X on its back, it is a latifasciatus.

Repetitive, rhythmic, call – like someone repeatedly running a scissor over a grinding wheel (I suppose).

|

N. pruinosus fulvus

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. winnemanna

|

N. linnei

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. robinsonianus

N. winnemanna

|

N. auriferus

N. canicularis

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

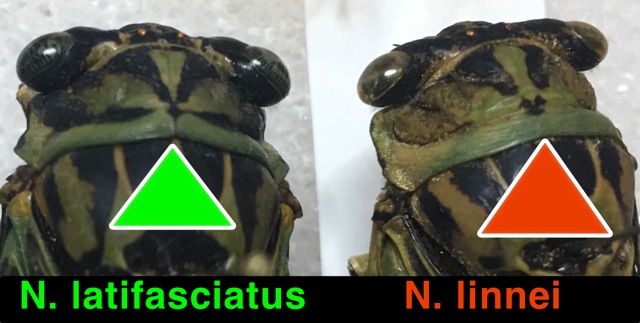

N. linnei (Smith and Grossbeck, 1907) aka Linne’s Cicada

Known for the bend of their wing.

Linne’s cicada’s call builds up — a crescendo — peaks, and then fades back down.

|

N. tibicen australis

N. tibicen tibicen

It sounds like the N. tibicen species, but unlike them, it calls from high in the trees.

|

N. latifasciatus

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. robinsonianus

N. winnemanna

|

N. auriferus

N. canicularis

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

| N. pruinosus fulvus Beamer, 1924 aka Yellow morph of Scissor Grinder.

This cicada should look like the other cicadas in this table, but its coloring is more yellow than green, like a teneral Scissor Grinder.

|

N. latifasciatus

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. winnemanna

|

|

|

| N. pruinosus pruinosus (Say, 1825) aka Scissor(s) Grinder

The Scissor Grinder looks a lot like Linne’s Cicada but their wing doesn’t have the bend that Linne’s Cicada has. The Scissor Grinder also seems to have more of an orange coloration to the “arches” on its mesonotum.

Its call is like N. latifasciatus, but it is faster paced.

|

N. latifasciatus

N. pruinosus fulvus

N. winnemanna

|

N. latifasciatus

N. linnei

N. robinsonianus

N. winnemanna

|

N. auriferus

N. canicularis

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

| N. robinsonianus Davis, 1922 aka Robinson’s Annual Cicada or Robinson’s Cicada

Robinson’s Cicada looks like Linne’s Cicada with less of a wing bend, and a different call.

Its call is kind of like N. latifasciatus, but much more raspy.

|

|

N. latifasciatus

N. linnei

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. winnemanna

|

N. auriferus

N. canicularis

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

| N. winnemanna (Davis, 1912) aka Eastern Scissor(s) Grinder

Like the Scissor Grinder, the Eastern Scissor Grinder seems to have more of an orange hue to the arches on its mesonotum, perhaps even more so than the Scissor Grinder.

Its call is similar to the Scissor Grinder.

|

N. latifasciatus

N. pruinosus fulvus

N. pruinosus pruinosus

|

N. latifasciatus

N. linnei

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. robinsonianus

|

N. auriferus

N. canicularis

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

Neotibicen canicularis (Green Group) and Neotibicen davisi (Southern Dog Day Group) compared. Photo by Paul Krombholz

Southern Dog Day

| Cicada |

Sounds Like |

Looks Like |

Looks Kind of Like |

| N. auriferus (Germar, 1834) aka Plains Dog-day Cicada

Coloration varies from rusty browns to greens.

Sounds like an angle grinder tool grinding something.

|

N. canicularis

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

N. davisi davisi

N. davisi harnedi

|

N. canicularis

N. latifasciatus

N. linnei

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. robinsonianus

N. winnemanna

|

| N. davisi davisi (Smith and Grossbeck, 1907) aka Davis’ Southeastern Dog-Day Cicada

Sounds like an angle grinder tool grinding something.

|

N. auriferus

N. canicularis

N. davisi harnedi

|

N. auriferus

N. davisi harnedi

|

N. canicularis

N. latifasciatus

N. linnei

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. robinsonianus

N. winnemanna

|

| N. davisi harnedi Davis, 1918

Sounds like an angle grinder tool grinding something.

|

N. auriferus

N. canicularis

N. davisi davisi

|

N. auriferus

N. davisi davisi

|

N. canicularis

N. latifasciatus

N. linnei

N. pruinosus pruinosus

N. robinsonianus

N. winnemanna

|

| N. superbus (Fitch, 1855) aka Superb Dog-Day Cicada

This cicada is the most unique looking: solid green with prominent yellow arches on its back.

|

|

|

|

| N. similaris (Smith and Grossbeck, 1907) aka Similar Dog-Day Cicada

This cicada is similar to the Neotibicen tibicen species in shape (hump back) and coloring.

|

|

|

N. tibicen tibicen |

Swamp Cicadas / Morning Cicadas

Swamp Cicadas are often the easiest cicadas to find because they prefer to stay in the lower branches of trees. Listen for one, and you’ll likely be able to spot it in the tree above you.

| Cicada |

Sounds Like |

Looks Like |

Looks Kind of Like |

N. tibicen tibicen (Linnaeus, 1758) aka Swamp Cicada

Swamp Cicadas are are known for their rounded, humped back. Their coloration varies from mostly black & some green to black, brown and green. Their collar is usually black, but can include green. N. tibicen tibicen – From Davis 1918: “Central area of the abdomen not black beneath, often pruinose, as well as the long opercula. Collar black, often with a greenish spot on each side near the outer angles.”

N. tibicen australis – From Davis 1918: “Central area of the abdomen not black beneath, often pruinose, as well as the long opercula. Collar all green or nearly so, as well as the pronotum and mesonotum.”

Its call builds up — a crescendo — peaks, and then fizzles out.

|

N. linnei

N. tibicen australis

|

N. tibicen australis |

N. similaris |

| N. tibicen australis (Davis, 1912) aka Southern Swamp Cicada

Southern Swamp Cicadas look like Swamp Cicadas, but they are more colorful. Their collars are often green & black.

Its call builds up — a crescendo — peaks, and then fizzles out.

|

N. linnei

N. tibicen tibicen

|

N. tibicen tibicen |

N. similaris |

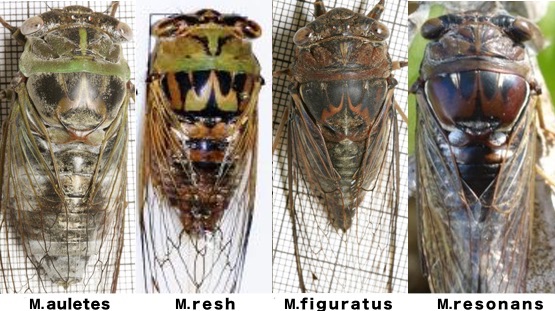

Lyric compared to Swamp Cicada

Top: Swamp Cicada; Bottom: Lyric Cicada. Note the more rounded shape of the Swamp Cicada’s mesonotum, and its green eyes; and the flatter shape of the Lyric cicada’s mesonotum, and its black eyes. Photo by me.

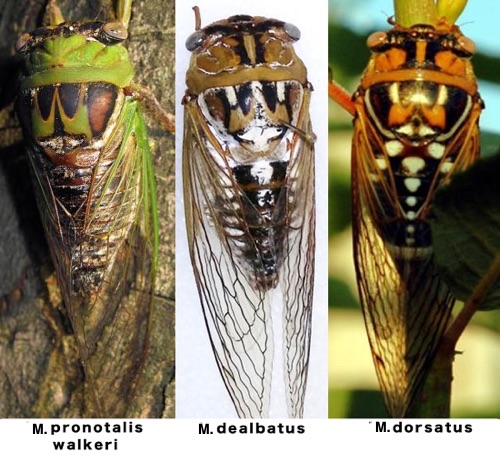

Lyric Cicadas

The Lyric Cicadas all look physically similar, but their coloration is unique enough to tell them apart. They usually have brown/black collars, which makes it easy to tell them apart from the “Green” Neotibicen. They also resemble the Swamp Cicadas, but Lyric cicadas have flatter mesonotums.

Two Dark Lyric Cicadas on Left, and a Lyric Cicada on the Right.

Photos L or R: Dan M, Roy Troutman, Dan M.

| Cicada |

Sounds Like |

Looks Like |

Looks Kind of Like |

| N. lyricen engelhardt (Davis, 1910) aka Dark Lyric Cicada

The Dark Lyric Cicadas have the darkest coloration of all the Lyric cicadas. Their mesonotum is almost entirely dark brown/black. They have a “soda-pop pull-tab” or keyhole shape on their pronotum.

Its sound is like an angle grinder tool steadily grinding a slightly uneven surface.

|

N. lyricen lyricen

N. lyricen virescens

|

|

N. tibicen tibicen

N. lyricen lyricen

N. lyricen virescens

|

| N. lyricen lyricen (De Geer, 1773) aka Lyric Cicada

The Lyric cicada, like most small Neotibicen, has a green, black & brown camouflage look, but the key is Lyric cicadas typically have black collars.

Its sound is like an angle grinder tool steadily grinding a slightly uneven surface.

|

N. lyricen engelhardti

N. lyricen virescens

|

|

N. tibicen tibicen

N. lyricen engelhardti

N. lyricen virescens

|

| N. lyricen virescens Davis, 1935 aka Coastal Lyric Cicada

The Coastal Lyric cicadas can be distinguished from other Lyric cicadas by their vibrant turquoise-green colors.

Its sound is like an angle grinder tool steadily grinding a slightly uneven surface.

|

N. lyricen engelhardti

N. lyricen lyricen

|

|

N. tibicen tibicen

N. lyricen engelhardti

N. lyricen virescens

|

1Molecular phylogenetics, diversification, and systematics of Tibicen Latreille 1825 and allied cicadas of the tribe Cryptotympanini, with three new genera and emphasis on species from the USA and Canada (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha: Cicadidae) by Kathy B. R. Hill, David C. Marshall, Maxwell S. Moulds & Chris Simon. 2015, Zootaxa 3985 (2): 219—251. Link to PDF.

3 Cicadas of the United States and Canada East of the 100th Meridian.

4Bug Guide.net’s Dog Day Cicadas Page.

###

I will update & augment this article over time.

For more information about these cicadas, visit the North American Cicadas page .